In this month's Sky Notes:

- Planetary Skylights

- Meteor Activity

- Mark's "Stellar Baker's Dozen challenge"

- March's Partial Solar Eclipse

- The Lion and the Serpent

- April 2015 Sky Charts

Planetary Skylights

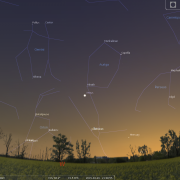

Venus, the brilliant evening star, dominates the evening western twilight sky, moving up through the winter constellation of Taurus as the bull slips down toward the western horizon. Over the course of the month Venus passes between the two open star clusters in Taurus, the Pleiades or seven sisters on the 11th and the Hyades from the 13-16th. Aldeberan, the fiery eye of the bull, will lie to the left of Venus. Telescopically Venus is best observed in bright twilight, reducing the glare of the planet somewhat. You should then be able to detect the gibbous phase of the planet. The young crescent moon is nearby on the 21st.

Venus, the brilliant evening star, dominates the evening western twilight sky, moving up through the winter constellation of Taurus as the bull slips down toward the western horizon. Over the course of the month Venus passes between the two open star clusters in Taurus, the Pleiades or seven sisters on the 11th and the Hyades from the 13-16th. Aldeberan, the fiery eye of the bull, will lie to the left of Venus. Telescopically Venus is best observed in bright twilight, reducing the glare of the planet somewhat. You should then be able to detect the gibbous phase of the planet. The young crescent moon is nearby on the 21st.

Mars continues to slide down toward the western horizon lower right of Venus and is passed by elusive Mercury travelling the other way on the 22nd. By the end of the month Mars will finally be lost in twilight.

Mars continues to slide down toward the western horizon lower right of Venus and is passed by elusive Mercury travelling the other way on the 22nd. By the end of the month Mars will finally be lost in twilight.

Mercury pops into the sky after mid month reaching almost 10 degrees altitude above the west horizon before falling back in early May. After passing Mars on the 22nd Mercury then pays the Pleiades a visit at the end of April and start of May residing to the lower left of the 'sisters' You will need to look around 8:45pm -9:15pm less than a binocular field above the west horizon. The moon passes through this part of the sky from the 19th to the 21st.

Mercury pops into the sky after mid month reaching almost 10 degrees altitude above the west horizon before falling back in early May. After passing Mars on the 22nd Mercury then pays the Pleiades a visit at the end of April and start of May residing to the lower left of the 'sisters' You will need to look around 8:45pm -9:15pm less than a binocular field above the west horizon. The moon passes through this part of the sky from the 19th to the 21st.

Jupiter is well placed to the south as twilight falls and should be on everyone's observing list. The dance of the Galiean moons is of particular interest, especially as they are strung out in a line like individual pearls this year. The moon passes by on the 25/26th

Jupiter is well placed to the south as twilight falls and should be on everyone's observing list. The dance of the Galiean moons is of particular interest, especially as they are strung out in a line like individual pearls this year. The moon passes by on the 25/26th

Saturn is steadily improving in the dawn sky and by mid month begins to rise before midnight. The ringed wonder lies above ruddy Antares, chief star in Scorpius. The moon passes close by on the 8th.

Saturn is steadily improving in the dawn sky and by mid month begins to rise before midnight. The ringed wonder lies above ruddy Antares, chief star in Scorpius. The moon passes close by on the 8th.

Meteor Activity

A number of lesser meteor showers occur during April. The Virginids and alpha Scorpiids each have zenith hourly rates (ZHR) of around half a dozen, equating to average sporadic meteor activity levels. The Virginids peak on April 7/8th but will be hampered by a waning gibbous moon. The Scorpiids peak on the 27th. but you will have to up before dawn to spot any.

The month's most prolific shower, the Lyrids, peak in the early morning hours of the 23rd this year. Zenith Hourly Rates are around the 25 mark and as it will be a 'no moon' period actual observed rates could reach 15 from 2am - 4am, with perhaps 7-10 beforehand. Lyra; the constellation radiant, will be located low in the NE during the evening, and high to south before dawn. The observer would therefore concentrate on other areas of the sky, not the radiant area.

The Stellar Baker's Dozen Challenge

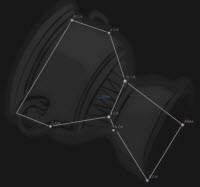

The lighter evenings of April offer up an interesting stellar challenge, testing the observing dexterity of astronomers - casual or otherwise in a race against time. No, this is not a 'faint fuzzy blob' hunt, like the Messier marathon, the exact opposite in fact, more of a sprint really. This is all about spotting first magnitude stars; those ranked brightest in the sky at the same time.

Piercing the spring twilight dotted around the sky, no less than thirteen are currently visible (we will count Castor), more than at any other time of year. However the window of opportunity in which to identify these stellar jewels rapidly diminishes as we head deeper into April, from little over an hour at the start, to just fifteen minutes by mid month.

5-Minute Stellar Baker's Dozen Challenge of 1st Magnitude Stars (by Mark Dawson)

Click for full-size image with Key.

You will require clear views right around the horizon and complicating matters further, a number of bright planets may confuse the unwary.

Let us assume it is April 8th, at which time twilight deepens around 9pm. Our first port of call lies over in the west, where the mighty hunter Orion is about to lose his right toe, marked by bright Rigel, (1) below the horizon. But, you also need to spot Spica (2) low in the south east when Rigel is above the horizon, so you will need to be quite sharp in doing this. Got both? Good. Now look above Orion's three belt stars which are aligned parallel to the west horizon, to locate the conspicuous orange hue of Betelgeuse (3). A hand span to the right of Betelgeuse and slightly closer to the horizon another orange star, Aldebaran (4) chief star in Taurus is visible in the 'V' of the Hyades cluster. A word of caution here, the brilliant 'star' visible in the W is in fact the planet Venus, and both Mars and Mercury will also be visible to the lower right towards the end of the month. Low in the WSW the brightest proper star in the sky - sparkling Sirius (5) is quite unmistakable.

Having picked out this first clutch of stars, there is no time to waste, so raise your gaze somewhat higher, to pick out the next wave of luminaries. Starting in the SW again seek out the bright solitary white hue of Procyon (6) in Canis Minor located above Sirius and to the left of Orion. Due west and higher still, Castor (7) and Pollux (8) denote the twins of Gemini, which is descending feet first down toward the horizon. At a similar altitude to Gemini further across in the WNW and above Venus, shines brilliant Capella (9) in Auriga, the only one of our bright seasonal winter stars not to set, being circumpolar from our latitude. Capella will spend the summer months arcing low above the north horizon.

Turn and face due south, where midway up you will encounter bright Regulus (10) in the 'sickle' asterism of Leo. The prominent 'star' to the right of Regulus is Jupiter. Our next star is located due east, where brilliant Arcturus (11) in the constellation of Bootes is very noticeable, its soft orange hue contrasting markedly with Sirius, the only star of the baker's dozen brighter. Now for a test within a challenge, see how far into April you can spot both Sirius and Arcturus above the horizon at the same time.

We still have a couple of stars to indentify, so direct your gaze toward the north, where low in the NE brilliant steely blue Vega (12) resides in the constellation of Lyra. Vega almost rivals Arcturus in apparent magnitude, but unlike the 'guardian of the bear" it is circumpolar from Whitby's latitude. Our final star, Deneb (13) is located just above the NNE horizon and appears much less brilliant than Vega but is by far the most distant of the stars visited. It too is circumpolar and along with Vega constitutes two of the three stars forming the 'summer triangle'. In less than three months, only Arcturus, Capella, Deneb and Vega will remain of our original stellar baker's dozen, the rest having set. So, are you up for a fun observing challenge, it should only require 5 minutes (at most) to complete.

Solar Eclipse

You have to say that all things considered, we were rather fortunate to catch more than a fleeting glimpse of the partial eclipse on the 20th. The forecast did NOT make for pleasant viewing, but at least from Whitby the cloud fragmented just enough, and at the right time, for the greatest show ‘off earth’ to be viewed by the masses. From the Whitby pier band stand (our location for the event) light levels certainly dimmed, the temperature dropped, things seemed to go still, around the time of maximum obscuration- just after 9:35am. Even the seagulls fell quiet for a while!

You have to say that all things considered, we were rather fortunate to catch more than a fleeting glimpse of the partial eclipse on the 20th. The forecast did NOT make for pleasant viewing, but at least from Whitby the cloud fragmented just enough, and at the right time, for the greatest show ‘off earth’ to be viewed by the masses. From the Whitby pier band stand (our location for the event) light levels certainly dimmed, the temperature dropped, things seemed to go still, around the time of maximum obscuration- just after 9:35am. Even the seagulls fell quiet for a while!

Wherever you managed to watch it from, I hope you were as delighted, impressed and moved as we were, it will be another 11 years before another solar eclipse of similar magnitude will be visible from our shores, although a couple of lesser events will occur before then.

Have a look in the WDAS Gallery for some Members images of the Eclipse, and please e-mail us your own. Check-out this great animation by Keith D made from 54 images of the Eclipse.

The Lion and the Serpent

Lion v Serpent (Leo v Ophiucus)

Compared to the departing stellar canopy of winter, at first glance the spring sky may seem rather less inspiring. Yet, appearances can be deceptive and there is much to wonder at amongst the constellations now arranged across the south and east.

Our tour commences as darkness falls around 21:45h. By then Leo, the most readily identifiable spring constellation is located due south. The head and mane of the lion is marked by the distinctive star asterism known as the ‘sickle’, although some people view it as a backwards question mark. At the base of this arrangement shines prominent Regulus, Leo’s chief star, and faintest of the 1st magnitude stars. Regulus sits just above the ecliptic and as a consequence is sometimes occulted by the Moon and on very rare occasions by a planet.

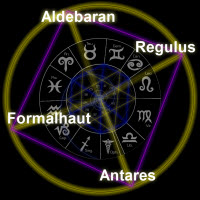

"Royal Stars of Persia"

Aldebaran (Taurus): Vernal equinox

Regulus (Leo): Summer solstice

Antares (Scorpio): Autumnal equinox

Fomalhaut (Aquarius): Winter solstice

In antiquity; from 4000 to 2000 BC Regulus was counted as one of the four Royal stars, those bright stars closest to the equinox and solstice positions. During this period Regulus was nearest the summer solstice position, but the effect of precession has subsequently shifted this point well away.

Constellation: Leo

To the left of the sickle, a ‘triangle’ of stars depicts the hindquarters of Leo. Just beneath an imaginary line joining Regulus to Denebola, the rearmost star of this triangle, a number of galaxies are found, some of which are visible under good seeing conditions in smaller scopes (see chart).

Constellation: Cancer

Ahead of Leo scuttles Cancer, faintest of the zodiac constellations the stars of which are often drowned out by moonlight or light pollution. Cancer is home to the fine open cluster M44 or Beehive, sometimes known as the Praesepe; ‘the ‘manger’. To the naked eye it appears as a misty patch, but a small scope reveals many individual stars.

Constellation: Hydra

Our next destination, Hydra – Water Serpent, is the largest constellation in the heavens, extending from below Cancer in the WSW, to beneath Virgo down in the ESE. Indeed it is well after 11pm before the entire constellation is visible. Hydra’s brightest star; Alphard- the ‘solitary one’, is located a hands span to the southeast of the distinctive, though rather faint, loop of stars marking the beasts writhing heads, visible to the right of Regulus.

In Greek mythology Leo, Cancer and Hydra are all associated with Hera, Queen of the gods. Both Leo and Hydra were raised as pets by Hera. Leo’s coat was said to be impervious to fire and metal weapons, whilst the multi-headed snake was empowered with the ability to re-grow heads should one be cut off. In the first of his twelve labours, Hercules, whom Hera despised, was tasked with slaying the lion beast ravaging the region of Nemea. He duly trapped the beast in a cave and clubbed it to death. In honour of this deed, Zeus placed the lion in the heavens.

Decidedly miffed by the loss of her pet, Hera then pitted Hercules against the multi headed Hydra, which he overcame by using flaming arrows to cauterise the neck-stumps thus stopping the heads from regenerating. Hera; who saw the snake was in trouble, sent a giant crab (Cancer) to assist Hydra. In the ensuing battle Hercules also crushed the giant crustacean. A distraught Hera then placed both monstrous creatures in the heavens.

Constellation: Corvus

Constellation: Crater

Toward the tail of Hydra, two small but original constellations rest on snakes body; Corvus the Crow and Crater the Cup. The outline of Crater is rather faint and therefore difficult to trace in light polluted skies. Corvus is more prominent; a quadrilateral grouping of stars that, mariners and astronomers alike refer to as ‘Spica’s Spanker’, a spanker being a type of sail nearby the bright star Spica. Corvus and Crater are linked by one legend in which Apollo sent his pet white crow to fetch a cup of water. The bird flew off with the cup in his talons, but tarried, waiting for the fruit of a fig tree to ripen. On his return Corvus tried to convince Apollo that Hydra the water snake had delayed him. Apollo did not believe the bird and in a rage turned the crow black, dispatching him to the sky close to Crater, which is just out of the thirsty bird’s reach. Next time we shall delve into the realm of the galaxies.

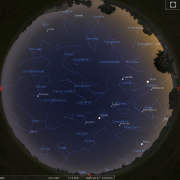

February 2015 Sky Charts

Click each image to see a full-size Sky Chart:

|

|

| Looking South Mid April - 21:30h |

Looking North |

|

|

| Looking East Mid April - 21:30h |

Looking West Mid April - 21:30h |

|

|

| Overview Mid April - 21:00h |

Image Credits:

- Planets and Comets where not otherwise mentioned: NASA

- Comet Lovejoy Position: Sky & Telescope Magazine

- Sky Charts: Stellarium Software

- Log in to post comments