In this month's Sky Notes:

- Planetary Skylights

- January Meteors

- Aurora Report & T Cor Borealis Update

- January Night Sky

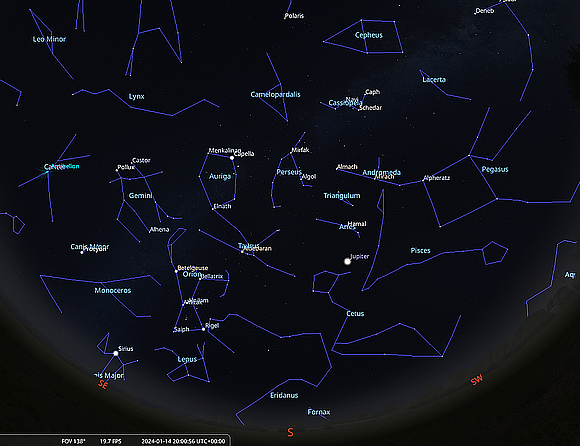

- January 2026 Sky Charts.

Planetary Skylights - Brief

Jupiter comes to opposition dominating the evening sky. Saturn and Neptune slip lower down in the SW. Uranus is well placed for observation below the Pleiades.

Dazzling Jupiter is the highlight of the month reaching opposition on January 10th and therefore visible all night. Jupiter crosses the meridian due south shortly after midnight, culminating an impressive 58-degrees in altitude equating to an observing window exceeding 12 hours for much of the month. Located in Gemini - the Twins, Jupiter's motion throughout January is retrograde - moving westwards relative to its stellar backdrop, taking it into the heart of the constellation ahead of Castor and Pollux, the twins lead stars.

Dazzling Jupiter is the highlight of the month reaching opposition on January 10th and therefore visible all night. Jupiter crosses the meridian due south shortly after midnight, culminating an impressive 58-degrees in altitude equating to an observing window exceeding 12 hours for much of the month. Located in Gemini - the Twins, Jupiter's motion throughout January is retrograde - moving westwards relative to its stellar backdrop, taking it into the heart of the constellation ahead of Castor and Pollux, the twins lead stars.

At magnitude -2.68 Jupiter is obvious to the naked eye, by far the brightest object in the night sky (Moon aside). ). It is a 'must see' object whatever sized observing instrument employed, exhibiting an oblate disk some 47 arcseconds in diameter crossed by darker belts and zones. The darker equatorial belts will be readily visible in instruments of 60mm (2.5”) aperture, with the less evident polar regions apparent in 80mm (3.4") instruments. Larger apertures show increasingly finer details including the northern and southern temperate belts. Surprisingly, for the largest planet, Jupiter's rotational period is just under 10 hours and given that the nightly observing window exceeds 10 hours all month, one full rotation may be observed.

When turned in our direction, look for the great red spot (GRS) - a colossal hurricane type feature visible on the south equatorial belt. The GRS has been present since the invention of the telescope, but in recent decades has diminished in size by perhaps a third and become paler in hue. The GRS can be observed in 100mm (4”) scopes but will be more obvious with 150mm (6”) instruments at medium powers. It is favourably orientated towards Earth during the evening (19:00-22:00hrs) on the following dates. January 3rd, 5th, 8th, 10th, 15th, 20th, 22nd, 25th, 27th & 29th, although depending what time you do observe, it can be seen every night in January.

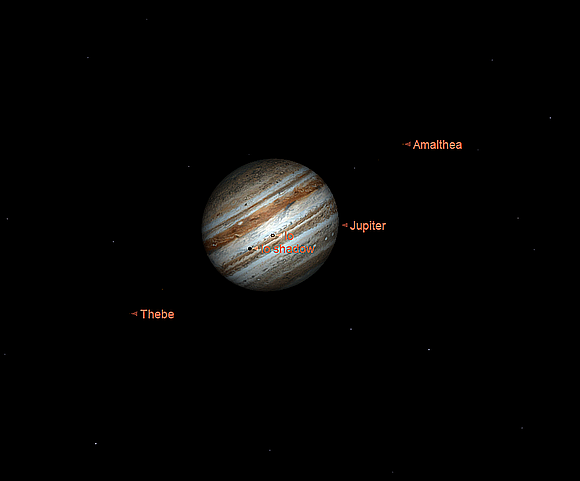

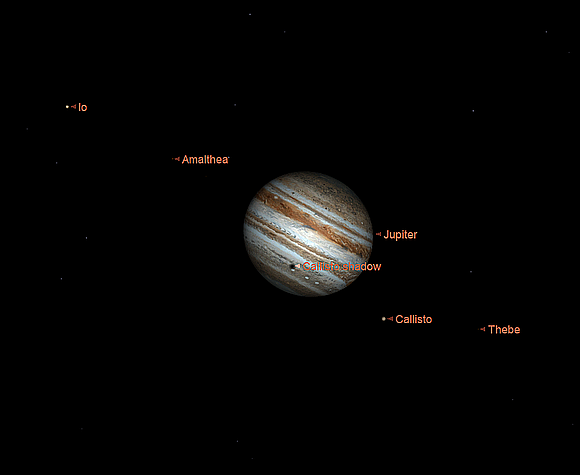

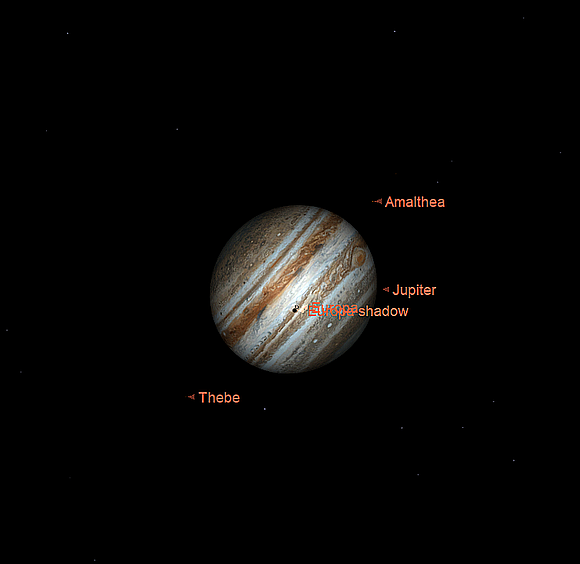

The view in the eyepiece is further enhanced by the Galilean moons - Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, visible as bright specks flanking the disk. Observe Jupiter regularly and you will note the 'dance' of these moons around Jupiter, throwing up a different configuration each night. Look for moon shadow transits (visible as black dots transiting the disk of Jupiter) which are particularly fascinating to follow. With good ‘seeing’ conditions, apertures exceeding 100mm (4") using medium/high magnification should suffice. The moons themselves are more difficult to spot as they pass in front of Jupiter, requiring larger apertures.

The most favourable evening shadow transits in January are Io - Jan 7th & 30th @ 21:30hrs and Jan 23rd @ 20:00hrs. Europa - Jan 11th @ 18:30hrs & 18th @ 21:30hrs. In the early morning hours, a rare transit of Callisto occurs on Jan 27th between 02:00hrs - 04:00hrs. A transit of Ganymede, with Ganymede itself present occurs on Jan 7th, 02:30hrs - 05:00hrs.

Saturn remains accessible for observation throughout much of January, although by the end of the month it is setting around 20:30hrs GMT from UK latitudes. The best views of Saturn will therefore be afforded earlier in the evening at the start of January. At magnitude +0.84, Saturn appears conspicuous against the fainter stellar backdrop of the Pisces/Aquarius border - a region devoid of brighter stars. Having spent several weeks in Aquarius, Saturn re-crosses back into Pisces around mid-month. Saturn is just shy of the celestial equator, which it finally crosses in the spring of 2026, unseen from view being in conjunction with the Sun.

Saturn remains accessible for observation throughout much of January, although by the end of the month it is setting around 20:30hrs GMT from UK latitudes. The best views of Saturn will therefore be afforded earlier in the evening at the start of January. At magnitude +0.84, Saturn appears conspicuous against the fainter stellar backdrop of the Pisces/Aquarius border - a region devoid of brighter stars. Having spent several weeks in Aquarius, Saturn re-crosses back into Pisces around mid-month. Saturn is just shy of the celestial equator, which it finally crosses in the spring of 2026, unseen from view being in conjunction with the Sun.

The image of Saturn’s rings through the eyepiece is normally a captivating one, however the rings are presently less than half a degree open, last year being a 'ring plane crossing year'. The view may be unfamiliar for occasional observers, with little substantial change to the appearance until later in 2026. Saturn will then also be north of the celestial equator. With the rings closed-up, larger apertures will reveal several of Saturn’s satellite moons normally hidden by the rings glare, Dione, Rhea, and Tethys should all be visible with modest-sized telescopes. Titan—by far Saturn’s largest moon—is typically seen as a nearby point of light.

Uranus is well placed to track down in the evening sky approximately 4 degrees lower right of the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus. At mag +5.6 Uranus is technically visible to the naked eye from exceptionally dark locations in the UK, although a good star chart or App may be necessary to verify. Binoculars will show it as a speck, but apertures of 80mm plus (3"+) are required to spot the very small 3.7 arcsecond grey-green disk. Instruments above 150mm (6") will clearly reveal this. After spending December near the pairing of 13 and 14 Tau (both 5th magnitude stars), Uranus spends January slowly edging away from them continuing its retrograde motion. Uranus culminates over 50 degrees above the south horizon, not setting until almost dawn.

Uranus is well placed to track down in the evening sky approximately 4 degrees lower right of the Pleiades star cluster in Taurus. At mag +5.6 Uranus is technically visible to the naked eye from exceptionally dark locations in the UK, although a good star chart or App may be necessary to verify. Binoculars will show it as a speck, but apertures of 80mm plus (3"+) are required to spot the very small 3.7 arcsecond grey-green disk. Instruments above 150mm (6") will clearly reveal this. After spending December near the pairing of 13 and 14 Tau (both 5th magnitude stars), Uranus spends January slowly edging away from them continuing its retrograde motion. Uranus culminates over 50 degrees above the south horizon, not setting until almost dawn.

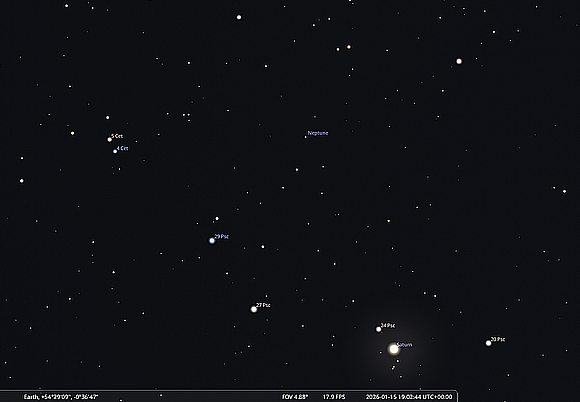

Neptune is well placed to track down in the early evening sky until mid-month, thereafter it will become increasingly mired in poorer seeing. Neptune has a magnitude of +7.8 and is visible as a faint ‘star’ when viewed through binoculars. A telescope will be required to positively identify the outermost planet, its tiny 2.8 arcsecond blue-grey disk visible in instruments of 100mm (4") aperture employing high magnification. Apertures exceeding 150mm (6") will reveal it more clearly. Starting the new year approximately 3-degrees upper left of Saturn, this separation diminishes to 1 degree 45-arcminutes by the end of January as Saturn creeps closer to Neptune in prograde motion. The nearest designated stars to Neptune are 29 & 27 Psc, both 5th magnitude and only just visible to the naked eye from semi urban sites. Like Saturn, Neptune is setting by 20:30hrs by the end of the month.

Neptune is well placed to track down in the early evening sky until mid-month, thereafter it will become increasingly mired in poorer seeing. Neptune has a magnitude of +7.8 and is visible as a faint ‘star’ when viewed through binoculars. A telescope will be required to positively identify the outermost planet, its tiny 2.8 arcsecond blue-grey disk visible in instruments of 100mm (4") aperture employing high magnification. Apertures exceeding 150mm (6") will reveal it more clearly. Starting the new year approximately 3-degrees upper left of Saturn, this separation diminishes to 1 degree 45-arcminutes by the end of January as Saturn creeps closer to Neptune in prograde motion. The nearest designated stars to Neptune are 29 & 27 Psc, both 5th magnitude and only just visible to the naked eye from semi urban sites. Like Saturn, Neptune is setting by 20:30hrs by the end of the month.

January Meteors

Meteor activity remains high as the New Year offers up one of the big three meteor showers - the Quadrantids, with a ZHR peak rate topping 100. The shower is named after the now defunct constellation of Quadrans Muralis, removed from sky charts in 1922, but used to lie at the junction between Hercules, Boötes and Ursa Major. The Quadrantids are the least observed of the major meteor showers, factors such as timing, weather, and a short peak duration of just a few hours at play here. The Quadrantids 'meteoroid' stream is constantly evolving, with the orbit appearing to oscillate up and down relative to the plane of the Ecliptic. During the early centuries AD, the shower stream was encountered in July as an Aquarids radiant! The shower was then missing for over a thousand years before reappearing in the 1700s again. The shower will again be 'lost' in another 300-400 years.

Minor Quadrantid activity ranges from late December until Jan 12th, but rapidly diminishes to sporadic levels after Jan 6th. During the evening of January 3rd, the shower radiant is positioned low to the North and few meteors will be seen. The short-lived peak occurs in the early morning hours of the 4th, by which time the radiant will be positioned over 40 degrees above the ENE horizon.

Peak Zenith Hourly Rates can exceed 100 under ideal circumstances, but don't expect to view anything like that number this year with a large waning gibbous Moon present drowning out many examples. Should skies be clear in the early morning hours an observer may expect to witness perhaps 10-15 meteors per hour. Quadrantids can be bright, sometimes blue, or green in hue. You will not require any additional optical assistance; the naked eye is quite sufficient.

The Geminid meteor shower in December was impacted by cloud over the peak night on the 13/14th - although the night of the 12th/13th was clear. Richard Randle managed to capture quite a few examples on this date using time lapse and composite techniques - as can be seen below. Rather excellent!

A composite image of Geminids - early morning hours of 13th.

Image - Richard Randle. (Click for full image)

Richard will be divulging more at the January meeting.

A Time lapse image looking north with a Geminid meteor.

Image - Richard Randle. (Click for full image)

Aurora Report

Auroral activity was noted on a few occasions in December, with a couple of displays sighted and imaged by society members. The first, on December 3rd did not reach the intensity levels predicted - at least at the latitude of North Yorkshire, appearing as a green band low to north for several hours in the evening. Bright Moonlight also impacted visibility. Mark did manage some handheld camera shots from the West Cliff, but by the time he'd returned home, collected a tripod and found a better location, the display had subsided.

Aurora - Dec 3rd around 19:30hrs GMT looking north from West Cliff - Whitby.

Hand held OM 1 - 9mm leica f1.7, 2 sec exp, ISO 3200. (Click for larger image)

Aurora subsiding, around 20:00hrs. Same equipment details as above.

Image - Mark D. (Click for larger image)

Perhaps unexpectedly, a second display lasting several hours occurred on the evening of December 12th. Given that skies were clear (and not aware of the display at the time), Mark had driven over to Saltwick Haven Holiday Park to try out a camera filter. It was only when his eyes had become better dark adapted, he noticed a glow to the North.

Looking East around 20:15hrs, Orion, Taurus, Gemini and Jupiter. Equipment details as above except tripod mounted and ISO 8000. (Click image to view fully)

And turning just 90 degrees looking north...

Looking to the North 20:45hrs, aurora clearly visible when imaged. Camera details as others,

Olympus 12-40mm (12mm) f2.8 lens, ISO 5000, exp 8 sec. (Click image for full picture)

On this occasion, having the right equipment, Mark managed to capture the display before it began to subside around 21:30hrs. Although perhaps not obvious to anyone glancing at the sky from more light polluted locations, the display was noticeable from darker ones. Do keep tabs on aurora alert websites, there is still plenty of opportunity to catch a display this winter.

T Corona Borealis - Update

Astronomers are still nervously waiting on the recurrent nova T Coronae Borealis to go nova. Nicknamed 'the Blaze Star', T CrB, or T Cor Bor was expected to do so last year, but it’s now looking like 2026. The star, which is a binary, is in the constellation Corona Borealis and is normally a 10th magnitude object requiring a telescope to identify. Previous positively observed eruptions in 1866 and 1946 had suggested an 80-year cycle - the star brightening to +2 in magnitude - easily visible to the naked eye.

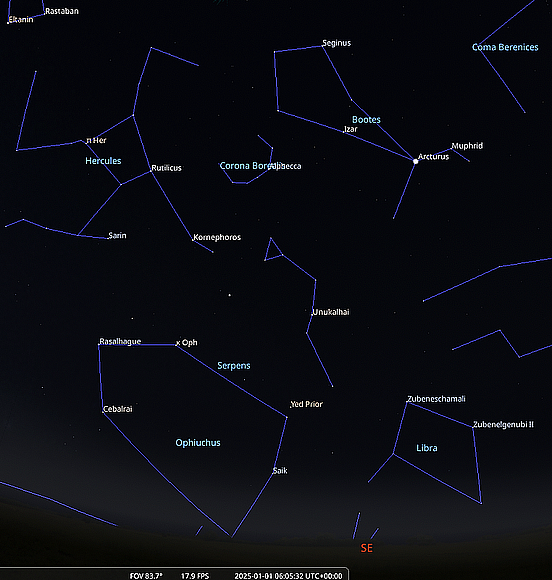

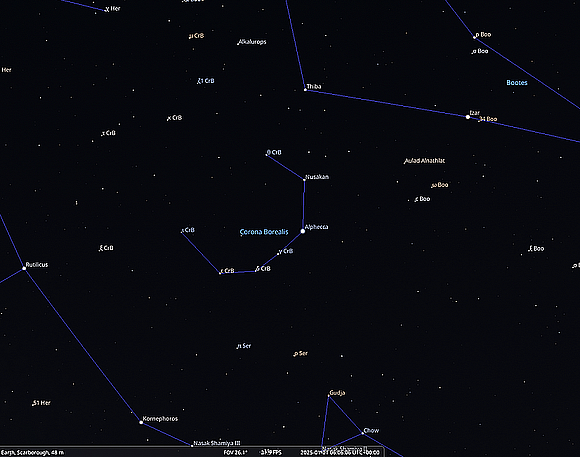

General location chart for Corona and Boötes in morning sky around 06:00hrs GMT.

(Click for full image)

The expected dip in brightness observed at the two previous documented events pre-eruption occurred in 2023 leading astronomers to suggest a late 2024 or early 2025 eruption date. Neither happened. Speculative dates in March and November of last year also passed without incident, so the waiting continues. Scientists now think the 80-year period may be fractionally variable, but who knows! Should the nova erupt in the coming weeks, the morning sky is where you will need to look – Corona located quite high to the NE by 06:00hrs. By late March Corona will be visible in the late evening sky once again.

Keep tabs across the media, it will be a headline news item when T Cor B finally does erupt, and it will only be a naked eye star for around a week. Ignore sensationalist reports of it lighting up the sky - it is not a supernova, just a nova, but the nature of the outburst is nevertheless impressive, it’s not every day we get to observe a star suddenly brighten.

January Night Sky

December presented two distinct weather patterns: the first half was primarily dominated by westerly or south-westerly winds, resulting in mild, unsettled, and wet conditions. The latter half saw the influence shift to easterlies, bringing colder and drier weather, although clear skies remained scarce along the east coast throughout the month. In contrast to recent years, the forecast for January suggests a wintrier flavour – at least initially, particularly for northern and eastern regions, though this remains subject to change.

We can be sure whatever the nature of conditions experienced this month; the starry dome above does not lie, offering consistency in the night sky as winter constellations dominate centre stage.

As dusk falls, the southern and western aspects of the night sky are still populated by seasonal autumnal constellations. The great square of Pegasus occupies much of the SSW, the orientation of the winged horse tilted down toward the horizon. Located below Pegasus, the less conspicuous constellations of Aquarius and Pisces are found with Cetus the whale (the Kraken in mythology) located just above the south horizon below Pisces. Use the front two stars in the square to locate the 'Krakens' brightest star - Diphda. Saturn currently resides on the Aquarius/Pisces border.

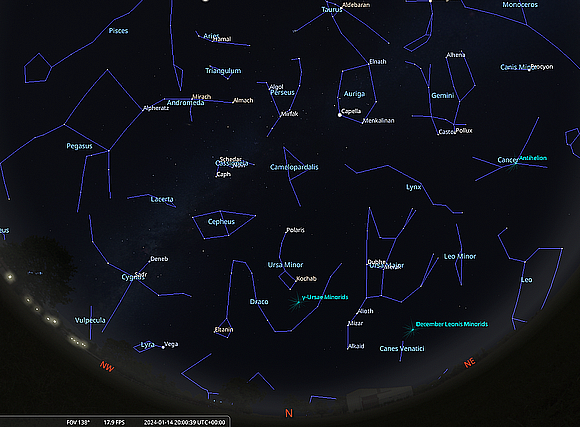

Meteorologically and astronomically speaking, winter it may be, yet summer constellations still cling to the margins of the west-northwest aspect, stars associated with the summer triangle still visible until the second week in January when Altair in Aquila finally departs. This leaves the remaining two circumpolar members of the asterism (Vega and Deneb) arcing perilously close to the north horizon overnight. During early evening hours look for Deneb sitting atop the crucifix form of Cygnus (sometimes referred to as the northern cross) above WNW horizon. The sparkling steely-blue presence of Vega, the most conspicuous of the summer triangle stars resides lower in the NW.

Facing the northern aspect during early evening note the familiar ‘saucepan’ asterism of the Plough, part of Ursa Major, balancing on its handle above the NNE horizon. The rear 'bowl' stars of Plough; Dubhe and Merak, can be utilised to track down the pole star; Polaris - due North. The 'North star' resides at the tail end of Ursa Minor - the Lesser Bear. The celestial dragon, Draco winds its way between the two bears - towards the NNW, where the head of the beast is marked by an irregular quadrilateral of stars not far from Vega. Overhead, the zenith position is occupied in turn by the distinctive ‘W’ pattern of Queen Cassiopeia, followed later by Perseus (the outline of which resemble a distorted figure Pi symbol) and then the stars of Auriga the charioteer, highlighted by brilliant Capella, which lies just shy of the zenith at 22:00hrs. The faint stars of Lynx slink after the charioteer.

It is however to the south and east where the observer's gaze is treated to an array of imposing constellations rich in mythology and observational interest. Leading this wondrous stellar cavalcade is the constellation of Taurus the Bull, in which lie the two open star clusters of the Hyades and Pleiades. Prominent ruddy Aldebaran - 'the eye of the bull’ is the most conspicuous stellar presence in the Hyades, a ‘V’ or arrowhead arrangement of stars, although at 67 light years, Aldebaran is not a genuine member, a foreground object lying at half the distance of true Hyades member stars.

Further west of the Hyades, the Pleiades star cluster (Seven Sisters) is truly a beautiful sight in binoculars or low power eyepiece. It is one of the most youthful clusters by stellar standards. Keen sighted observers can make out more than seven stars with the naked eye, although most people see five or six. Binoculars, or very low telescopic magnifications reveal dozens of stars, and the entire cluster contains well over 300 members approximately 410 light years away.

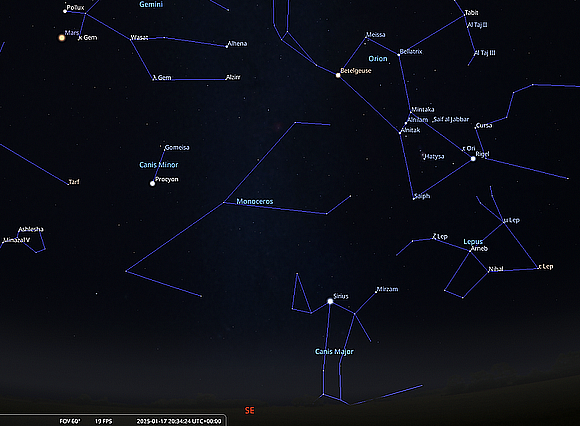

By late evening the constellation of Orion - the mighty hunter, stands proud at the heart of the glittering tableau ranged across the southern aspect. The main outline of the hunter is quite distinct; three stars in a sloping line set amid a larger rectangle bounded by 4 others. Two of these stars, in opposing corners are genuine super luminaries. Rigel illuminates the bottom right of the rectangle, a B7 class blue/white star at least 60 thousand times more luminous than our Sun.

The top left corner is marked by the orange hue of Betelgeuse, a red super-giant star already ballooned to gargantuan proportions, over 500 million miles in diameter and with one foot in the stellar grave. Betelgeuse is likely to go supernova, perhaps within the next 10-20 thousand years, hopefully sooner. Rigel is also on a similar path to ultimate destruction, a few tens of millions of years in the future, a short life span by stellar standards.

Situated beneath the three stars marking Orion’s belt sits one of the great show piece objects in the night sky, the Orion nebula, one of the nearest regions associated with stellar birth at around 1270 light years. The Nebula consists of a huge cloud of gas and dust in which new stars are “born”. Seen clearly as a misty smudge through binoculars, telescopically the nebula is quite breathtaking in the right instrument, a swirl of nebulous cloud at the heart of which reside a trapezoid-shaped asterism from which the cluster gets its name, the Trapezium, the four “bully boys” of this stellar crèche. The brightest members are found within 1.5 light years of each other and have estimated solar masses of between 15 and 30 times our Sun. These young OB stars are luminous X-ray sources and are also responsible for much of the illumination of the surrounding nebula. The Trapezium stars are very young, under a million years and perhaps little more than 300,000 years old. They are easily seen through the eyepiece of most telescopes.

Upper left of Orion, stand the Twins of Gemini, marked by the two conspicuous stars, Castor, and Pollux. Castor, the most northerly of the pair, is slightly fainter than twin brother Pollux which shines with a pale amber lustre. Although Castor appears solitary, it is a multiple system comprising 6 stars of which the brightest two components may be separated with modest scopes, given stable atmospheric conditions. Jupiter currently resides within Gemini.

The two hunting dogs of Orion, Canis Major, and Canis Minor, dutifully follow their master across the heavens. The belt stars of Orion point down in the general direction of Canis Major and toward the most prominent of all night stars, sparkling Sirius, seen low to the SE. Some distance above and left, solitary Procyon, in the lesser dog of Canis Minor, is yet another highly conspicuous winter jewel, the prominence of both primarily due to proximity; 8.6 and 11 light years respectively.

The dog’s quarry, the timid celestial hare of Lepus, may be traced crouching below Orion just above the southern horizon. Look for the faint glow of the winter Milky Way which passes down to the left of Orion, separating the two dogs on opposing banks. A few of the faint stars set amidst this milky haze comprise the heavenly unicorn of Monoceros an inconspicuous constellation, but full of deep sky wonders. To the lower right of Orion, the waters of the river Eridanus marked by the star Cursa (beta eri), rise next to Rigel. The faint constellation erratically meanders towards Cetus in the SW before cutting back below Lepus, plunging down through the horizon continuing well into the southern hemisphere ending at the brilliant star Achernar far to south. Not surprisingly Eridanus is the longest, (though not largest by area) constellation in the entire heavens.

Finally, by the month’s end the celestial shoots of Spring have well and truly sprouted, making inroads into the late evening sky away from the eastern horizon The faint stars of Cancer the Crab scuttle after Gemini marking an unseen border of seasonal change from Winter to Spring. Leo the lion, the signature group of spring follows, identified by the ‘Sickle’ asterism at the foot of which shines bright Regulus. Some way below Procyon in Canis Minor, a faint, but distinctive stellar loop denotes the head of Hydra, the largest constellation in the heavens. Spring will have bloomed long before the entirety of Hydra will be visible in the evening sky, but you can get a sneak peek by stepping outside and viewing south around 05:00hrs!

For the time being though we have the glorious winter sky to explore. Choose your instrument; binoculars, telescope or even the naked eye, wrap up well and enjoy the free vista.

January 2026 Sky Charts

Additional Image Credits:

- Planets and Comets where not otherwise mentioned: NASA

- Sky Charts: Stellarium Software and Starry Night Pro Plus 8

- Log in to post comments